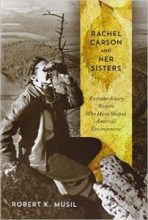

Rachel Carson and Her Sisters: Extraordinary Women Who Have Shaped America's Environment, By Dr. Robert K Musil, Rutgers University Press; First Paperback Edition, 2015, 256 pages.

Could it be that Rachel Carson, for all her contributions as a scientist, environmentalist, activist, and purveyor of wonder, is a token female? Was she the first woman to have an impact on environmentalism? She has been remembered; she remains controversial, but she was not the first or last significant woman to have an impact on the movement to care for the biotas of our delicate planet.

In  2007, Dr. Musil heard talk show hosts Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh spew fresh attacks on Carson more than four decades after she died of breast cancer. Why the venom? Musil’s question prompted a reading of Silent Spring and several biographies. He realized that there “had been a lot of Rachel Carsons.” These women have faced attacks and been largely relegated to obscurity, yet this linage of women still fights for the life on Earth.

2007, Dr. Musil heard talk show hosts Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh spew fresh attacks on Carson more than four decades after she died of breast cancer. Why the venom? Musil’s question prompted a reading of Silent Spring and several biographies. He realized that there “had been a lot of Rachel Carsons.” These women have faced attacks and been largely relegated to obscurity, yet this linage of women still fights for the life on Earth.

Musil begins with Rachel Carson and those who influenced her: the most important –her mother. Maria McLeon Carson, influenced by her own mother, instilled in Rachel an “emotional identification with birds and nature and a penchant for careful observation and scientific method.” Musil identifies more than a half century of accumulated writings and discoveries by women who built the platform of Carson’s life work.

Four years before Thoreau published Waldon, Susan Fenimore Cooper was America’s first popular nature writer. Her 1852 `Rural Hours was as popular as Silent Spring in its day. Perhaps it’s not surprising that this romantic chronicle of natural progressions of the seasons in Upstate New York has fallen out of favor. Without direct outrage, Musil seems to suggest that there is an injustice to Susan Coppers literary contributions, which also includes then-famous essays and poems, being lost in the folds of history. The lineage of wonder and lamentation in the nature writing surely goes back to this shadowy figure from the past.

Musil ties lines of implication through his tales making this book more than a collection of mini-biographies. For example, the reader comes to understand that Susan F. Cooper published in magazines such as St Nicholas and little Rachel Carson was reading that same magazine. Although their lives did not overlap, their values did.

Inequity permeates the life of many of Musil’s should-be-famous subjects. America’s first female professional ornithologist was able to briefly penetrate the male world of scientific study of birds and published a volume of Natural History of Birds. When her singular male mentor and advocate died, she was relegated to outsider status. Florence Miriam, who became the first student environmental organizer and a source inspiration to the sport of bird-watching, couldn’t get a science degree from Smith College because the women’s college didn’t have a full science major. In 1889 her first book, Birds through the Opera Glass, suggests a startling change to the sport of bird-watching: how about we watch the birds without shooting them?

As female naturalists were able to study and write, their scope of contribution widened under their glass ceiling. Women such as Alice Hamilton, who is the “mother of industrial toxicology and the founder of pollution toxicology,” fought to protect every living thing against the dangers of benzene and mercury as early as 1916. Mary Amdur studied particles in the air and their dramatic and deleterious effect on guinea pigs and humans—but when she attempted to publish her findings in 1956, she was strong armed by tough-guys in leather jackets and threatened by her Harvard University superior to withdraw her paper or be fired. She refused and was fired. She continued to study, publish and promote green initiatives and did influence the scientists who, years later, admitted “She got it right years before the rest of us.”

Strong -arm tactics against women scientists litter the accounts of women at work in environmental science. Davra Davis PhD, as presented by Musil, seems to be half scientist, half warrior, which we all should be thankful for. She participated in hundreds of studies, authored books and did her best to protect people from pollutants. She’s the scientist who convinced the Federal Aviation Administration to ban smoking on planes. Despite her collected evidence about harm to human lungs, the ban was passed only when she identified that the “gunky yellow stuff” also fouls the engines and instruments in the aircraft.

Accounts of these women and many more weave a sense of wonder with science and a sensitivity to truth. If there are things that the nation needs as much as environmental intelligence, those things are critical thinking and truth. For example, Musil notes about three quarters through the book that vitriol toward Carson is rooted in the claim that she is responsible for genocide by malaria in Africa after the banning of DDT. “DDT was not immediately banned, as a few cranks have contended.” It was granted a public health exception and phased out as alternatives were developed. The nation would indeed be a far superior place if it were more informed by Musil and his extraordinary “sisters” than by the noise of shills , exploiters, polluters, strong-armers, and cranks. Everyone should read this book.

, exploiters, polluters, strong-armers, and cranks. Everyone should read this book.

Amy Lou Jenkins is the author of Every Natural Fact: Five Seasons of Open-Air Parenting. This review first appeared in the Sierra Club's Muir View. Contact Jenkins through this site if you’d like to offer a book for possible review.