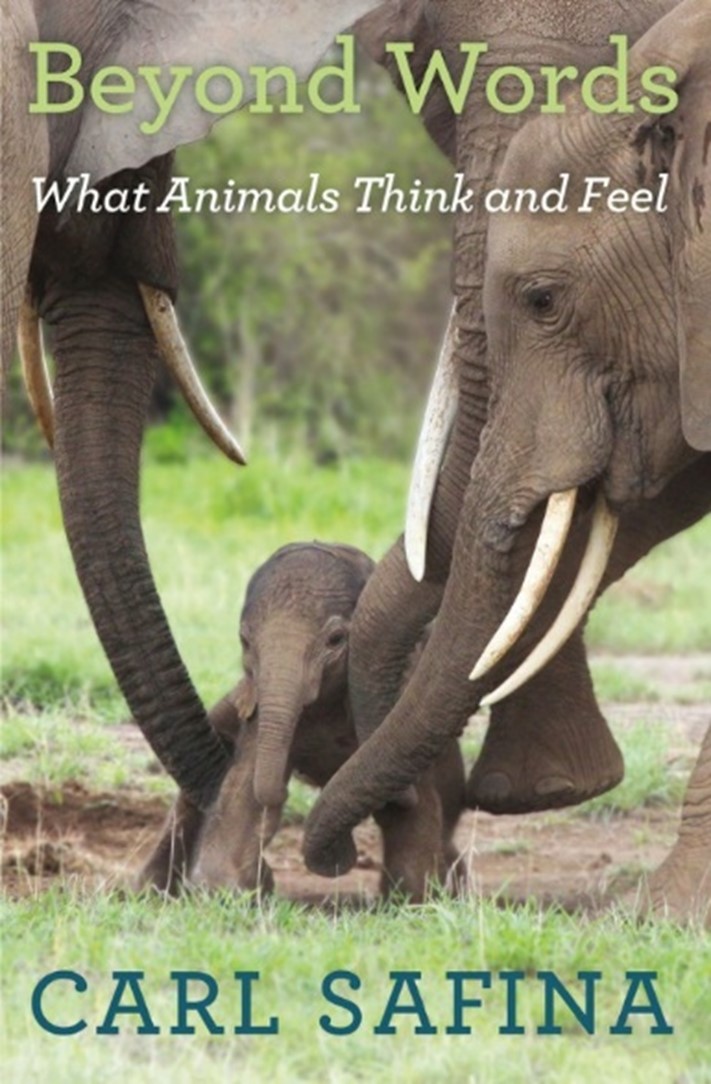

Book Review of 'Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel' by Carl Safina

Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel, by Carl Safina, Henry Holt Co., 2015, 480 p.

Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel, by Carl Safina, Henry Holt Co., 2015, 480 p.

Many scholars from those enrolled in Middle School General Science to PhD professors have been exposed to and likely held the standard that prohibits anthropomorphizing animal behaviors. Students are told to observe behaviors without attribution of human emotion or any emotion. Even in English class many are held to a criterion that requires calling beloved family pets by the pronouns “it” or “that.” Fluffy and Fido aren’t graced with the grammatical designation of the human “who.” This is a standard that Jane Goodall rejected during her PhD studies, going against the scientific tide. With obvious satisfaction, Carl Safina reports that Goodall got her papers published, even with the grammatical nonconformance.

In Beyond Words, Safina acknowledges the importance of scientific inquiry and objectivism, but questions scientific dictums that have discredited scientists who might gather evidence like “the mother elephant positioned herself between her baby and the alligator” and then draw conclusions such as “to protect her calf.”

Safina deftly argues that scientist have specific knowledge about the common structures and developments of mammalian brains. Conclusions have long been a part of the scientific process, so why has scientific culture slapped the hands of scientists who make scientific conclusions about the inner life of animals?

Perhaps, Safina suggests, humans have reached beyond objectivity to protect a self-inflated view of the human animal. We may have a bias that our rich inner life and our communicative interactions as more worthy and soulful than any other creature. We have denied animals the scientific existence of personality and emotion. We have kept our human status as separate and perhaps superior. Beyond Words does not strive to call out animal behaviors as human, rather it seeks to evaluate and study the lives of animals with an attempt to cast off the ego constructs that have been applied to the scientific study of animals.

Embedded with researchers, much in the way reporters live with soldiers during war coverage, Safina shares stories of researchers, species, historical trends, and individual animals. The layering of these points of view builds credibility and intimacies with animal species and individual animals. Readers travel to Amboseli National Park in Kenya to learn of elephants trying to survive drought and poaching. Researchers have known these elephants as individuals for decades. Cynthia Moss, described as “a young woman in her seventies” has been observing these elephants for four decades without on smidgeon of field weariness. She knows the individuals, who [SIC] is a good mother, who is impulsive, and who is silly and playful. These highly social mammals have taught humans something of their language and relationships. Researchers now can recognize some of the words such as the sound made to indicate “bees.”

In Yellowstone, the wolves have reclaimed and supported wilderness with the balance that a top predator brings, but much like the famed Cecil the Lion, they are often shot when they travel away from the park. Can we see wolves as conscious beings who have bonds, ambitions, and the arc of a career? The evidence is credible. Researchers are discovering clues to understand the consciousness of wolves, but the studies are fraught with tales of individual wolves with sad endings at the hands of humans. This outcome is especially sad given that wolves and humans have forged bonds with evolutionary consequences that have resulted in extreme bonds between species. How can “man’s best friend” have evolved from the reviled wolf? The individuality of wolves transforms the scientist’s attempt to give the wolf a number instead of a name, but the life of the canine transforms the number to a name. When Alpha 21 died and his pack was scattered and lost, the lamentations spoken for the name 21 were no less than if the famous wolf were named Henry.

Safina’s stories of whales chronicles amazing and inexplicable behavior. While maintain scientific objectivity, he questions why whales don’t knock people out of their tiny boats. Why would a whale guide humans to shore, or toss ice onto a ship deck after a snowball was tossed to him? Claiming to be a “hard-hearted disbeliever of things unknown” Safina doesn’t draw conclusions from what he calls “Woo-woo” stories. Yet he tells the stories. These stories are not antithetical to scientific study; scientists do share and publish case reports. These stories are evidence.

Beyond Words doesn’t draw all the conclusions, but it makes an entertaining and credible case for the rich lives of animals. The book is opulent with amazing tales as well as scientific analysis. Conclusions are both offered and withheld. Readers who spend time with Safinia’s words will begin to see themselves as not separate from animals, but part of a rich network of species and individuals.

Contact Amy using contact box below to forward books for possible review. A version of this review first appeared in the Sierra Club's Muir View.

Books of Interest

From Jack Walker Press and other esteemed publishers

LitFriends: The Summer of Personal Writing

Call for Submissions: New Anthologies JWP 2024

1 thought on “Book review of ‘Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel’”